Artists Network, Blog, In the News

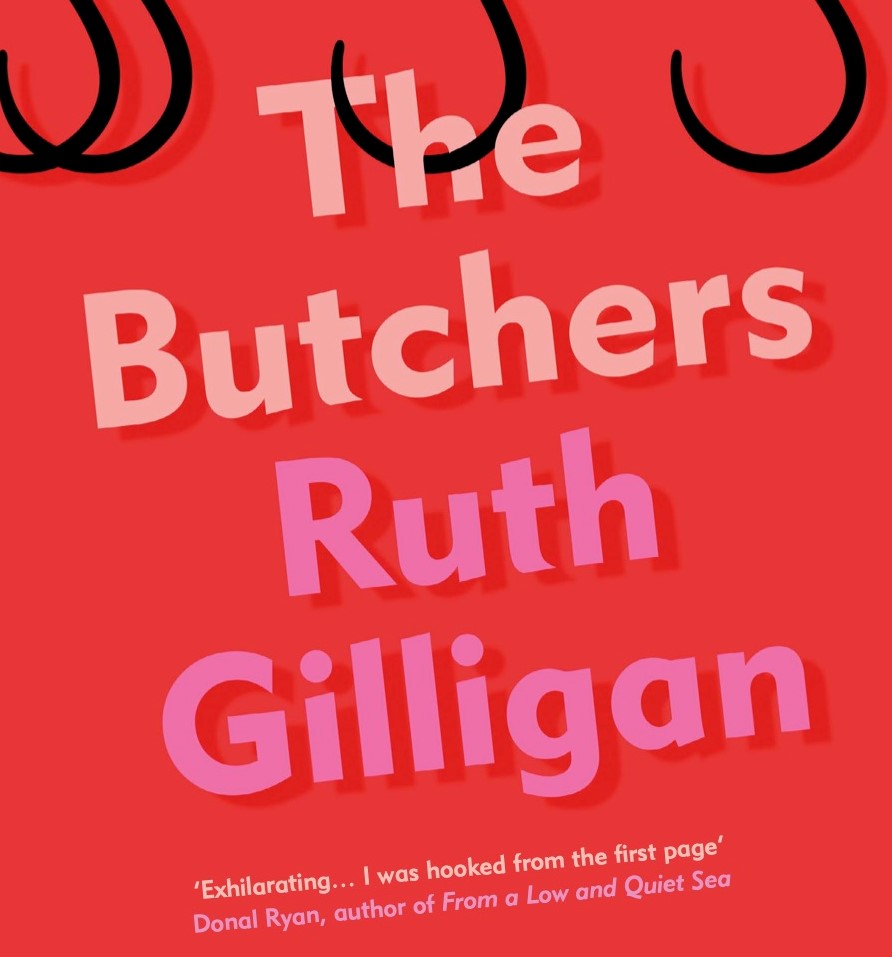

Ruth Gilligan and The Butchers

Ruth Gilligan is a Narrative 4 Artist and Global Master Practitioner, born in Dublin and based in the UK. Her novel The Butchers is out today in the UK and Ireland. We had the opportunity to chat with Ruth about her new book and how she’s handling the new social distancing normal.

Want more from Ruth? Check out her recent feature in The Times.

*

Tell us about The Butchers.

The Butchers centres around a murder in the Irish borderlands in 1996. I chose that year because it is such an interesting point in Irish history—divorce has just been legalised; the first rumblings of the Celtic Tiger are beginning to show – there’s a real sense of forward progress. At the same time, many people are still wedded to Ireland’s old traditions; still believe in the ancient folklore and superstitions. It’s a fascinating tension.

1996 was also the year of the BSE—or ‘Mad Cow Disease’—crisis, so all across Britain entire herds were falling sick then being slaughtered and burned on these giant pyres. Ireland only had a few cases, but there was still all sorts of dodgy stuff going on – cattle smuggling, black market deals, elaborate money laundering scams; it makes a wonderful backdrop for a novel.

What’s one question about the book no one’s asked yet?

I’ve sort of just done it myself, but people tend to focus on the novel’s context; the real-world facts and events that feature throughout the book. But I want them to ask me about the characters—there are four points of view in total, a mother and daughter, and a father and son—and each one has their own storyline; their own particular secrets and desires. Forget about the cows—let’s talk about them!

How did you get involved with Narrative 4?

In 2013 I was reading an interview with Colum McCann and he mentioned that he had founded this new organisation which used storytelling to try and foster empathy. Shortly afterwards, I started my job as a university lecturer so I decided to send a random email to the N4 website. Two days later, I’m on Skype with [Narrative 4 Director of Global Programs] Lee Keylock; two months later, I’m in Belfast watching a story exchange between a girls’ Protestant school and a girls’ Catholic school; from that point onwards, I was pretty much hooked.

How have you been changed by your work with Narrative 4? And what change have you witnessed a in others, as a result of their involvement?

I’ve been profoundly changed in so many ways, but for me the most rewarding thing is seeing the change in others. In 2018 I ran a big project between teenagers from the UK and Ireland; this was right in the middle of all the Brexit carry-on. Some of the British kids are now studying at my university and they tell me—apart from the empathy and the connections—N4 has done wonders for their own self-worth. They had been dreading university—as young Muslim women, they said they found new people and new situations overwhelming; felt as if they were always being perceived a certain way—but thanks to the story exchange, they took it all in their stride and are now thriving.

In this time of social distancing, how are you staying connected to your community?

Like so many of us, I seem to spend my life now in front of a screen—working, socialising, visiting family – my computer is my only connection with the outside world. This isn’t as grim as it sounds—on Saturday night I had a ‘glass of wine’ with my oldest school friends and we had two people dialing in from Dublin, two from California, one from New York, one from Australia and me dialing in from London. It was amazing! In all our years of living apart, we’ve never done that before; sometimes it takes a crisis to consolidate the best laid plans.

I’ve also been struck by the number of kind messages I’ve received from people I don’t usually hear from—just checking in or, as they say, ‘reaching out’ (I’ve never loved how that phrase has been colonised by business-speak, but in certain moments, it can feel completely apt—the act of extending a kind hand; of offering a tender embrace).

Finally, I do believe fiction is a way to ‘stay connected’; to remind ourselves of the texture of life – of different lives – rather than us all just being reduced to ‘patients’ and ‘key workers’ and ‘vulnerable parties’. It can be difficult to empathise with statistics, whereas stories demand that we engage with humanity’s endless multiplicities. Books allow us to ‘dial in’ across every border.